5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Heavy Marine Equipment Reinforcement

5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Heavy Marine Equipment Reinforcement: A Structural “Spring” in a Saltwater World

When naval architects and offshore engineers talk about reinforcement materials, they rarely think in terms of “springs.” Yet that is exactly the most revealing way to understand the role of 5083 marine aluminum bar in heavy marine equipment: not as a rigid, immovable spine, but as a controlled, corrosion‑resistant spring that absorbs, distributes, and rebounds from repetitive loads in a brutally corrosive saltwater environment.

Steel fights the ocean by brute strength and sacrificial corrosion allowance. 5083 marine aluminum, especially in bar form, takes a subtler path: a balance of high strength, low weight, corrosion resistance, and weldability, tuned through alloy design and tempering. For cranes, A‑frames, winch beds, ROV handling systems, davits, and deep‑sea lifting structures, this alloy becomes the metallic “buffer” between dynamic forces and structural failure.

Below is a deep, technically grounded look at 5083 marine aluminum bar as a reinforcement material, from the perspective of load management and microstructural stability in harsh marine service.

Why 5083 Bar Reinforces Heavy Marine Equipment Differently

Most discussions of 5083 focus on plate for hulls or decks. But in bar form, the alloy operates in a more demanding mechanical landscape. Bars become the ribs, tie‑rods, gusset supports, and localized reinforcement cores that concentrate and redirect stress paths.

Seen from a load‑engineering perspective, 5083 bar delivers three critical functions:

- It redistributes short‑duration impact and cyclic loads from heavy equipment (such as active heave‑compensated winches) into a more uniform stress field.

- It mitigates fatigue accumulation by combining reasonable yield strength with good ductility and excellent weldability.

- It maintains those properties in a chloride‑rich environment where many high‑strength metals corrode, pit, or crack prematurely.

This “spring‑like” behavior is controlled mainly by its magnesium‑rich composition and its strain‑hardened tempers.

Alloy Design: The Magnesium Strategy for the Sea

The core design philosophy of 5083 is simple: use magnesium, not copper, to gain strength in a marine environment.

Copper is a great strengthener for aluminum but aggressively undermines corrosion resistance in chloride media. Magnesium, on the other hand, provides solid solution strengthening and a degree of strain‑hardening response while preserving—and in many environments enhancing—resistance to seawater.

A typical chemical composition of 5083 marine aluminum bar (mass percent) is:

| Element | Content (%) | Function in Heavy Marine Use |

|---|---|---|

| Mg | 4.0 – 4.9 | Primary strengthener; improves work‑hardening and corrosion resistance |

| Mn | 0.40 – 1.0 | Grain refiner; enhances toughness and resistance to cracking |

| Cr | 0.05 – 0.25 | Stabilizes microstructure; improves resistance to stress‑corrosion cracking |

| Si | ≤ 0.40 | Controlled impurity; excessive content can reduce toughness and weldability |

| Fe | ≤ 0.40 | Impurity control; kept low to avoid coarse intermetallics and corrosion sites |

| Cu | ≤ 0.10 | Minimized to avoid pitting and galvanic issues in seawater |

| Zn | ≤ 0.25 | Limited to maintain SCC resistance |

| Ti | ≤ 0.15 | Grain refinement; improves as‑cast structure |

| Others | ≤ 0.05 each, ≤ 0.15 total | Controls overall impurity level |

| Al | Balance | Base matrix providing low density and ductility |

From a reinforcement standpoint, the interplay between Mg, Mn, and Cr is the key. Magnesium gives the basic load‑carrying skeleton; manganese refines the grain size and dampens crack propagation; chromium suppresses harmful precipitate morphologies that could trigger stress‑corrosion cracking under tensile load in seawater.

Standards and Implementation: When “Marine Grade” Is Not Enough

To be credible in heavy marine reinforcement, 5083 bar cannot merely be “5083‑like.” It must meet strict compositional and mechanical thresholds defined by marine and aluminum standards.

Common international standards referencing 5083 bar include:

- EN 573 series for chemical composition of wrought aluminum alloys

- EN 485 and EN 754 series for mechanical properties and dimensional tolerances of wrought products

- ASTM B221 for aluminum and aluminum‑alloy extruded bars, rods, and profiles

- ISO 6361 for wrought aluminum sheets, plates, and strips (often used for cross‑reference on properties)

- Classification society rules (such as DNV, ABS, LR, BV) that often recognize 5083 as a marine structural alloy for hulls and superstructures

For heavy equipment reinforcement, the implementation standards most often focus on:

- Composition limits for Mg, Mn, Cr to ensure true 5083 behavior

- Mechanical property guarantees at specified thicknesses and tempers

- Ultrasonic or other NDT requirements for large cross‑section bars used in critical lifting or support components

- Traceability and heat‑lot documentation, particularly for class‑approved offshore gear

When specifying reinforcement bars for cranes or A‑frames on an offshore support vessel, for example, engineers may reference ASTM B221 5083‑H112, with tighter internal requirements based on DNV or ABS design rules for allowable stresses, weld joint efficiency, and fatigue detail categories.

Temper and Microstructure: Tuning the “Spring Rate” of 5083 Bar

Unlike age‑hardening alloys, 5083 gains its strength primarily through work hardening and solid solution strengthening. This means the temper selection is effectively a decision on how “stiff” or “forgiving” the reinforcement spring should be.

Common tempers for 5083 bar in marine reinforcement include:

- O (annealed) – Soft, maximum ductility, lower strength; useful where extensive forming is required before final assembly, or where impact absorption is more critical than yield strength.

- H111 – Slightly strain‑hardened from manufacturing; offers a gentle increase in strength with good formability. Often used for structural components that will be welded but still take moderate loads.

- H112 – As‑fabricated; properties are largely driven by the extrusion/rolling process; commonly specified for heavy sections and machined reinforcement blocks where strength needs are moderate but weldability must remain high.

- H116 – Specialized marine temper with controlled levels of work hardening and corrosion resistance requirements; often used for hull plating, but extruded bars in H116 may be used where higher as‑supplied strength and guaranteed marine corrosion performance are required.

- H321 – Strain‑hardened and then thermally stabilized; offers improved strength and dimensional stability in service, with a focus on resisting exfoliation and stress‑corrosion.

In design terms:

- O temper behaves like a low‑rate spring: large deflection, excellent energy absorption, lower peak load carrying.

- H116 and H321 behave like higher‑rate springs: higher yield strength and reduced deflection, suitable for reinforcement bars that must limit deflection under high static or cyclic load.

Mechanical Properties: How 5083 Bar Carries Real Marine Loads

Values can vary by standard and supplier, but typical room‑temperature mechanical properties for 5083 marine aluminum bar used in heavy reinforcement are:

| Temper | Typical Yield Strength Rp0.2 (MPa) | Typical Ultimate Tensile Strength Rm (MPa) | Elongation (A50, %) | Typical Brinell Hardness (HBW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | ~ 125 | ~ 275 | ~ 18 – 23 | ~ 75 |

| H111 | ~ 135 – 160 | ~ 275 – 300 | ~ 14 – 20 | ~ 75 – 85 |

| H112 | ~ 135 – 180 | ~ 275 – 320 | ~ 12 – 18 | ~ 80 – 90 |

| H116 | ~ 190 – 240 | ~ 300 – 340 | ~ 10 – 16 | ~ 90 – 95 |

| H321 | ~ 215 – 240 | ~ 305 – 345 | ~ 10 – 14 | ~ 90 – 100 |

For heavy marine equipment, these numbers translate directly into:

- Weight‑optimized support frames for deck cranes and davits that can meet classification yield limits with significantly lower mass than steel.

- Reinforced foundations for winches, windlasses, and towing pins where stiffness and fatigue resistance are critical.

- Load‑bearing members in ROV launch and recovery systems that must tolerate high cycle counts and splash‑zone corrosion.

What makes 5083 bar particularly compelling is the combination of reasonable yield strength with high elongation. Under dynamic wave‑induced loads or sudden shock, a component can elastically and slightly plastically deform, absorbing energy, rather than cracking in a brittle manner.

Corrosion Behavior: From Surface Film to Structural Reliability

In ocean environments, reinforced marine structures face three primary corrosion modes: general corrosion, pitting, and stress‑corrosion cracking (SCC). 5083 is engineered to resist all three more effectively than many alternative aluminum alloys.

A few distinctive aspects of 5083 corrosion behavior:

- The Mg‑rich solid solution, combined with low Cu and Zn, allows a stable, adherent oxide layer to form in seawater, limiting general corrosion rates even in continuous immersion.

- Properly selected tempers (H116, H321) are qualified specifically for resistance to exfoliation and SCC in marine atmospheres and splash zones.

For heavy equipment reinforcement, this translates to longevity in the most aggressive areas:

- Substructures located in the splash or tidal zone on offshore platforms.

- Reinforcement bars embedded in or bolted to deck structures where standing seawater and abrasives are common.

- Supporting members within wash‑down areas on workboats and OSVs where chlorides are constantly replenished.

The is not that 5083 is perfectly immune—it isn’t—but that its corrosion rate and damage mode are slow and predictable enough to be accommodated in design life calculations and maintenance plans, often with minimal or no coatings.

Weldability and Joint Strategy: The Real Test of a Reinforcement Alloy

Heavy marine equipment is rarely built from a single monolithic bar. It is an assembly of welded bars, plates, and machined blocks. An alloy that performs beautifully as a rolled bar but fails at welded joints is unacceptable.

With 5083, the weldability story is unusually favorable:

- It can be welded using common marine processes such as MIG and TIG with 5xxx series filler wires (5087, 5183, 5356, etc.).

- Joint efficiency is high when proper design and procedures are followed, allowing designers to use welded bars as integral parts of main load paths.

- The H‑tempers will partially soften in the heat‑affected zone, but the overall strength reduction is predictable, and design rules from classification societies incorporate this behavior.

From a reinforcement standpoint, a 5083 bar is more than its catalog tensile strength; its true value is in how that strength persists around welds and intersections. The alloy’s resistance to weld‑related hot cracking and its compatibility with common marine fillers make it a safer choice for highly loaded welded frames and support grids.

Dimensional Range and Forms for Heavy Reinforcement

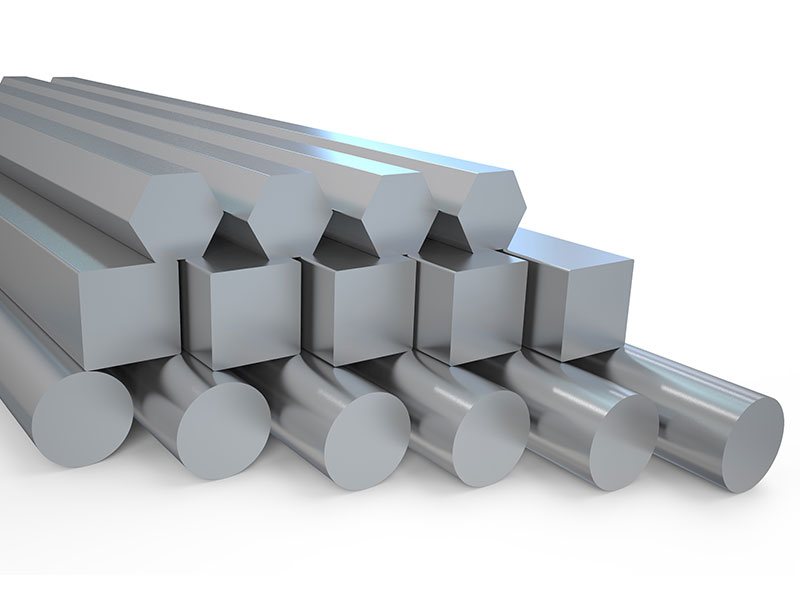

The term “bar” often hides how diverse the product actually is. For heavy marine equipment, 5083 bars are supplied in various forms:

- Round bars for pins, shafts, and clevis components.

- Flat bars and rectangular bars for stiffeners, edge reinforcements, and load‑distribution strips.

- Square bars for machined brackets, gusset blocks, and high‑load connectors.

- Custom extruded profiles where complex geometry—flanges, ribs, cable channels—is integrated into a single high‑efficiency cross section.

Typical size ranges include:

- Round bar diameters from about 10 mm up to over 300 mm, depending on the mill and standard.

- Flat bar thicknesses from around 6 mm to 100 mm or more, with varying widths.

- Rectangular bars for heavy machining stock, often specified by minimum cross‑section thickness and guaranteed mechanical properties.

This dimensional flexibility is crucial in reinforcement design. It allows engineers to:

- Place material exactly where moment of inertia is needed for bending resistance.

- Convert large, multi‑part welded steel fabrications into single extruded aluminum profiles with better fatigue performance and lower weight.

- Standardize bar sizes across different pieces of equipment for easier global sourcing and replacement.

The usual approach to reinforcement is simple: prevent yielding at all costs. In heavy marine systems, that traditional steel‑centric mindset can actually undermine reliability, because it overlooks how dynamic and variable loads truly are.

By using 5083 marine aluminum bar as the core reinforcement material, designers can adopt a more nuanced energy‑management philosophy:

- Allow small, recoverable deflections in reinforcement members to damp transient loads.

- Exploit the low density to move structural mass upward or outward without overloading foundations, improving stability and equipment reach.

- Use weldable, corrosion‑resistant bars to create latticed or trussed frames that can be easily modified, extended, or repaired in the field.

Under this philosophy, 5083 is not merely an alternative to steel; it is an enabler of different geometries and different responses. Reinforcement stops being just “more metal” and becomes a tuned, corrosion‑resistant system for capturing, redirecting, and surviving energy in a hostile marine environment.

Typical Applications in Heavy Marine Equipment

To see this philosophy in action, consider typical uses of 5083 marine aluminum bar in reinforcement roles:

- Deck crane pedestals and boom support girders where weight reduction improves vessel stability and fuel efficiency.

- A‑frame and gantry side legs, bracing members, and cross‑ties on survey and research vessels.

- Winch beds, towing point reinforcements, and fairlead supports that must withstand extreme line tensions and shock loads.

- ROV and subsea tool handling frames, including guide posts, lifting lugs, and structural backbones.

- Offshore platform access structures, ladders, and walkways where corrosion and maintenance access are chronic concerns.

In each case, 5083 bar provides a structural backbone that does not punish the vessel with extra deadweight, while still tolerating the violent operating cycles typical of offshore work.

Integrating 5083 Bar into a Marine Design Specification

To take full advantage of 5083 aluminum bar for heavy marine reinforcement, a well‑structured specification typically includes:

- Alloy designation: EN AW‑5083 or AA5083 with reference to applicable standards (EN, ASTM, ISO).

- Temper requirement: Often H112, H116, or H321 depending on load level, stiffness requirements, and corrosion criticality.

- Mechanical property minimums: Yield strength, UTS, and elongation values appropriate to bar size and standard.

- Corrosion and temper compliance: Reference to marine tempers (e.g., H116/H321) when exposure is severe.

- Welding procedure compatibility: Approved filler wires, prequalified joint types, and controlled heat input for predictable HAZ properties.

- NDT or inspection requirements: For high‑consequence structural bars—especially large‑diameter or thick sections—ultrasonic testing and dimensional checks.

When carefully integrated into the design framework, 5083 marine aluminum bar ceases to be a simple commodity and becomes a well‑defined, class‑compliant structural element.

Related Products

6082 marine aluminum rod & bar

6082 Aluminum Rods & Bars are extruded or rolled products manufactured from 6082 aluminum alloy — a thermally treated (typically T6 temper) aluminum-magnesium-silicon alloy that balances high tensile strength, good weldability, and excellent corrosion resistance.

View DetailsMarine aluminum hollow bars

Marine Grade Aluminum Hollow Bars are fabricated from high-quality alloys such as 5083, 5052, 6061, and 6082, all known for their exceptional resistance to seawater corrosion, salt spray, and marine atmospheres.

View DetailsMarine aluminum hexagonal bars

Marine Grade Aluminum Hexagonal Bars are produced from premium corrosion-resistant aluminum alloys such as 5083, 5052, 6061, and 6082.

View DetailsMarine grade aluminum solid bar

Marine Grade Aluminum Solid Bars are produced from premium aluminum alloys optimized for saltwater exposure, such as 5083, 5052, 6061, and 6082. These alloys offer unparalleled resistance to corrosion caused by seawater, salt spray, and marine atmospheres, while maintaining excellent mechanical strength and toughness.

View DetailsRelated Blog

5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Heavy Marine Equipment Reinforcement

5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Heavy Marine Equipment Reinforcement: A Structural “Spring” in a Saltwater WorldWhen naval architects and offshore engineers talk about reinforcement materials, they rarely think in terms of “springs.

View Details5083 5052 H32 60mm aluminum bar for boat

High-performance 5083 and 5052 H32 60mm aluminum bars tailored for marine applications. Ideal for boat building with excellent corrosion resistance, superior strength, and formability.

View Details5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Long Term Marine Equipment Support

Marine applications demand materials that can withstand harsh environments, conduct excellent performance, and provide durability for long-lasting use. One such product that has gained prominence in the marine industry is the 5083 Marine Aluminum Bar.

View Details5083 Marine Aluminum Hexagonal Bars for High Strength Shipbuilding Components

FeaturesHigh Strength: 5083 aluminum hexagonal bars offer superior strength-to-weight ratios, essential for maximizing load-bearing capabilities in marine applications.

View Details5083 Marine Aluminum Bar for Marine Equipment Reinforcements

Superior strength, corrosion resistance, and reliability of 5083 Marine Aluminum Bars, specifically engineered for marine equipment reinforcements. Ideal for harsh sea environments, these aluminum bars offer exceptional mechanical properties and long-term

View Details5083 Marine Aluminum Hexagonal Bars for Offshore Platform Construction

5083 Marine Aluminum Hexagonal Bars for Offshore Platform Construction5083 marine aluminum hexagonal bars offer high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and outstanding weldability for offshore platform construction.

View Details

Leave a Message