5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams for Saltwater Resistant Marine Ship Design

5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams: The Structural Spine of Saltwater‑Resistant Ship Design

Among all the aluminum profiles applied in marine engineering, 5086 marine aluminum I beams sit in a special category: they are not just another “section shape,” but the actual spine and rib cage of many saltwater vessels. Where plates define surfaces, I beams define intent. They express how a designer wants a hull to behave under load, in waves, and across decades of corrosion exposure.

Looking at 5086 I beams from the outside, they seem simple: an I‑shaped cross‑section, a known alloy, standard tempers. But when examined from a structural‑and‑corrosion co‑design viewpoint, these beams become a very precise answer to one question:

“How can we turn aluminum’s lightweight advantage into lifelong fatigue resistance in saltwater, without sacrificing weldability or repairability?”

Why 5086 Alloy for Marine I Beams?

Marine designers facing saltwater conditions juggle competing demands: high stiffness, fatigue resistance, low weight, easy fabrication, and long‑term corrosion resistance. 5086 aluminum, a non‑heat‑treatable Al‑Mg alloy, is a deliberate compromise tilted heavily toward durability in severe marine service.

In structural I beams, 5086’s advantages align with three critical needs in ship design.

Corrosion resistance built into the chemistry

At the core of 5086 is magnesium as the primary alloying element. This gives:

- Excellent resistance to chloride‑induced corrosion in seawater

- Strong immunity to stress corrosion cracking compared with many high‑strength aluminum alloys

- Very good resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion when properly finished and protected

For long, thin I beam flanges and webs exposed to condensation, bilge atmospheres, and splash zones, this in‑alloy protection means fewer unplanned inspections, fewer repairs, and a more predictable structural life.

Strength that doesn’t sacrifice weldability

5086 gains its strength from cold work (strain hardening), not from heat treatment. That has two direct implications for I beams:

- Welding does not trigger strength‑destroying microstructural transformations typical of heat‑treatable alloys

- The heat‑affected zone (HAZ) softening exists, but remains controllable and predictable; designers can account for it with rational safety factors and joint geometry

On a ship, nearly every major I beam is welded into longitudinal, transverse, and deck structures. The alloy must forgive localized heating, allow full penetration welds, and still maintain structural integrity under cyclic loading and seawater attack. 5086 is one of the few alloys that willingly checks all those boxes.

Stiffness and weight: shaping the dynamic behavior of the hull

Aluminum density is roughly one‑third that of steel. For I beams, that means:

- Larger section modulus at comparable weight

- Lower overall displacement and better payload capability

- Lower inertial loads on the hull structure in heavy seas

Instead of increasing plate thickness to gain stiffness, designers can strategically use 5086 I beams to create a stiff “skeleton” while keeping shell plating thinner. This separation of “skin” and “frame” is where aluminum ships gain their performance edge.

From a traditional perspective, hull and deck plates are the stars of the show. But a more realistic viewpoint, borrowed from fatigue analysis and operational maintenance, suggests that the beams and stiffeners determine whether a vessel stays within its design deflection and vibration limits over decades of use.

In that perspective:

- The web of a 5086 I beam is the shear diaphragm that reacts wave‑induced torsion

- The flanges are the bending flanges that carry global hull girder moments and local deck bending

- The alloy’s resistance to micro‑pitting and intergranular attack is directly tied to how long those bending and shear capacities remain intact under real seawater conditions

Errors in I beam selection and layout rarely show up in the first year. They show up in year ten, fifteen, or twenty, as fatigue cracks at weld toes, local corrosion thinning at condensation points, and subtle but escalating changes in vibration behavior.

Choosing 5086 I beams is effectively choosing a slower degradation curve under saltwater and cyclic loading.

Chemical Composition of 5086 Marine Aluminum

The chemical balance of 5086 is tuned to emphasize corrosion resistance, weldability, and stable mechanical properties across tempers. A typical composition range is:

| Element | Content (%) | Functional role in marine I beams |

|---|---|---|

| Mg | 3.5 – 4.5 | Primary strengthener; dramatically improves seawater resistance |

| Mn | 0.20 – 0.70 | Grain refinement; stabilizes properties; improves toughness |

| Cr | 0.05 – 0.25 | Controls grain structure; reduces susceptibility to corrosion |

| Si | ≤ 0.40 | Residual; controlled to protect weldability and toughness |

| Fe | ≤ 0.50 | Residual; kept low to reduce intermetallic phase‑driven corrosion |

| Cu | ≤ 0.10 | Minimized to avoid stress corrosion and galvanic sensitivity |

| Zn | ≤ 0.25 | Controlled to retain marine corrosion performance |

| Ti | ≤ 0.15 | Sometimes used for grain refinement during casting |

| Others (each) | ≤ 0.05 | Trace elements only |

| Others (total) | ≤ 0.15 | |

| Al | Balance | Forms the corrosion‑protective oxide film in marine environments |

The low copper and controlled iron/silicon levels are especially important in saltwater, because they reduce local galvanic micro‑cells that can accelerate pitting at stress concentrations in thin I beam sections and weld zones.

Mechanical Properties and Common Tempers for I Beams

5086 is a strain‑hardened alloy. That means mechanical properties are set by the amount and pattern of cold work, then often stabilized by a mild thermal treatment. For marine I beams, the most relevant tempers are:

- 5086‑O (annealed): maximum ductility, lower strength; rarely used for primary beams but may play a role in components requiring extensive forming

- 5086‑H111: lightly strain‑hardened; suitable where moderate strength and high formability are required

- 5086‑H112: as‑fabricated, with properties controlled but not tightly defined; common for extruded I beams with complex geometry

- 5086‑H116: strain‑hardened and partially annealed; specifically “marine hull” temper with enhanced resistance to exfoliation and stress corrosion

- 5086‑H32 / H34: moderate strain hardening with stabilization; used where higher yield strength is needed but not to the point of compromising weldability and toughness

Typical mechanical properties for a 5086 marine I beam (values approximate and dependent on product form, thickness and exact temper):

| Temper | Tensile Strength Rm (MPa) | Yield Strength Rp0.2 (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Typical Use in Marine Structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | ~ 240 | ~ 95 | ≥ 20 | Non‑critical formed parts, rarely for beams |

| H111 | ~ 270 | ~ 125 | ≥ 14 | Secondary stiffeners, formed profiles |

| H112 | ~ 260 – 305 | ~ 120 – 200 | ≥ 10 – 14 | Extruded I beams, general marine structure |

| H116 | ~ 275 – 320 | ~ 125 – 215 | ≥ 10 | Hull girders, naval and workboat structures |

| H32 | ~ 260 – 305 | ~ 215 | ≥ 10 | Higher strength beams with welded details |

In ship design calculations, these values are not used blindly. Designers account for:

- Reduction of mechanical properties in the weld and HAZ

- Fatigue strength under wave‑induced cyclic loading

- Impact toughness in low‑temperature marine service

The choice of temper for I beams reflects a balance between static design loads and long‑term fatigue and corrosion requirements.

Dimensions, Section Properties, and Practical Parameters

In marine practice, 5086 I beams are selected and customized not just by their nominal height and width, but by how their section properties interact with real hull loads.

geometric parameters for an I beam profile include:

- Overall depth (H)

- Flange width (B)

- Web thickness (tw)

- Flange thickness (tf)

- Root radius between web and flange

- Section area (A)

- Second moment of area (I) about major and minor axes

- Section modulus (W) about major axis

- Radius of gyration (i)

In aluminum ship design, a typical strategy is to:

- Use relatively wide flanges to maximize the section modulus for bending in deck or hull girder applications

- Keep web thickness optimized to handle shear while controlling weight

- Use generous root radii to reduce stress concentrations and improve fatigue life, especially around welded joints and cut‑outs

5086 extruded I beams are often produced to metric or imperial size ranges that harmonize with common plate thicknesses and stiffener spacing in marine classification rules. Custom shapes are also extruded for large series shipyards to align with their preferred structural philosophy.

Implementation Standards and Classification Requirements

Designing with 5086 marine aluminum I beams is never done in isolation. The alloy, temper, geometry, and fabrication methods are locked into a framework of international and classification standards.

Common material and product standards for 5086 include:

- ASTM B221: Aluminum and aluminum‑alloy extruded bars, rods, wire, profiles, and tubes

- ASTM B928/B928M: High magnesium aluminum‑alloy sheet and plate for marine service and similar environments (reference for hull‑grade behavior, H116)

- EN 573: Chemical composition of wrought aluminum and aluminum alloys

- EN 755: Extruded rod/bar, tube, and profiles – mechanical properties and tolerances

Marine classification societies bring additional guidance and acceptance criteria. Examples include:

- DNV‑RU‑SHIP and DNV‑RU‑HSLC: material requirements for aluminum structures, weldability, and inspection

- ABS Rules for Building and Classing Aluminum Vessels and High‑Speed Craft

- Lloyd’s Register Rules for the Application of Aluminum Alloys in the Construction of Ships

These rules guide choice of:

- Minimum yield strength and elongation based on service area and vessel type

- Permitted tempers and thicknesses for primary versus secondary structural members

- Welding consumables and procedures for joining 5086 I beams to plates and other extrusions

- Nondestructive examination methods and acceptance levels for welded I beam connections

The result is that a 5086 marine I beam is not just “5086‑H112 extrusion.” It is a certified component within a classification envelope, traceable from ingot to onboard location.

Alloy Tempering: Controlling Microstructure for Marine Performance

One of the more distinctive technical aspects of 5086 I beams is how temper selection controls microstructure and, with it, long‑term performance.

Since 5086 is non‑heat‑treatable, it does not follow the age‑hardening logic of 6xxx or 7xxx alloys. Instead, its strength depends on work hardening from rolling or extrusion plus optional stabilization anneals. For I beams, tempering addresses several subtle but important issues.

Balancing strength and ductility in the flanges and web

Heavier cold work can raise yield strength, which is attractive on paper. But excessive hardening can reduce ductility and toughness, especially at low temperatures, and can increase sensitivity to fatigue crack initiation at welded joints.

Marine practice tends to favor tempers such as H116 or moderate H112 for I beams where:

- Ductility in the flange and web remains sufficient to absorb local deformations

- Yield strength is high enough for the design loads and classification requirements

- Toughness in the as‑welded condition remains robust

Stabilizing the microstructure against stress corrosion

The “marine hull” tempers like H116 undergo controlled processing that:

- Reduces residual stresses

- Minimizes the risk of exfoliation corrosion in sheet and plate analogs

- Supports a more uniform response to welding heat input

For I beams, this means that after weld‑on integration into the hull girder or deck, the remaining residual stress pattern is more predictable and less likely to interact with saltwater to cause localized corrosion‑assisted cracking.

Weldability and Joint Design in 5086 I Beams

In aluminum shipbuilding, a material is only as good as the joint that connects it to the rest of the structure. 5086 is favored precisely because, for I beams, it behaves well in the welding shop and at sea.

Distinct welding characteristics include:

- Good compatibility with common marine filler wires such as ER5356 or ER5183

- Controlled softening in the HAZ, which designers can account for with joint detail and local reinforcement

- Low susceptibility to hot cracking when procedures are correctly followed

From a structural viewpoint, weld design around 5086 I beams typically:

- Aligns welds along low‑stress regions where possible, such as near the neutral axis instead of the flange outer fiber

- Uses scalloped cutouts and radiused transitions in brackets to avoid sharp stress raisers at the web and flange junctions

- Incorporates smooth weld toes and controlled weld leg sizes to reduce fatigue crack initiation under cyclic wave loading

Corrosion behavior of welded I beam joints is then addressed by:

- Choosing fillers compatible with 5086’s Mg‑rich matrix

- Using proper cleaning before welding to avoid porosity and oxide inclusions

- Applying suitable marine coatings, sealants, or cathodic protection depending on location (immersion, splash zone, or internal spaces)

Corrosion Resistance in Real Saltwater Service

It is tempting to view corrosion resistance as a simple label: 5086 = “good in seawater.” But in practice, the interplay between alloy, shape, and environment is much more subtle.

For I beams in marine structures, corrosion behavior is influenced by:

- Geometry: water traps at flange‑to‑plate intersections or bracket feet

- Drainage and ventilation: bilge spaces, double bottom compartments, and voids where humidity remains high

- Coating quality: completeness and durability of paint or anodic coatings on web corners and welds

- Galvanic couples: connections to other alloys or to stainless steel fittings and fasteners

The 5086 alloy brings several advantages to this situation:

- A strong, adherent oxide film that regenerates after mechanical damage, giving a self‑healing tendency in mildly aggressive conditions

- Good resistance to general corrosion in fully immersed seawater, especially when combined with cathodic protection

- Lower sensitivity to localized attack compared with copper‑bearing alloys, especially in crevices and at welds

From a maintenance viewpoint, the main benefit is that thickness loss in 5086 I beams tends to be gradual and predictable rather than sudden or localized. That predictability simplifies life‑cycle thickness surveys and repair planning.

Design Applications: Where 5086 I Beams Change the Equation

In modern marine and offshore structures, 5086 I beams are heavily used where strength, weight, and corrosion resistance must simultaneously be optimized.

Typical applications include:

- Longitudinal girders in aluminum hulls for high‑speed craft and patrol vessels

- Transverse frames and web frames in plate‑stiffened hull structures

- Deck girders and deckhouse framing for ferries, offshore support vessels, and yachts

- Support structures for superstructures and helicopter decks on otherwise steel ships

- Internal framing in passenger vessel accommodations where weight savings allow more payload or additional amenities

The choice of 5086 over alternative alloys like 5083 for certain I beam applications often comes down to:

- Projected welding intensity and expected HAZ properties

- Required combination of strength, ductility, and fatigue performance

- Yard experience and qualification with specific alloys and filler combinations

By using 5086 I beams, designers gain enough strength to meet classification requirements while still preserving aluminum’s advantages: low weight, excellent corrosion resistance, and straightforward fabrication.

Manufacturing and Quality Control Considerations

The performance of a 5086 marine I beam is as much about how it was produced as about its nominal alloy designation. Manufacturing steps affect microstructure, residual stresses, geometry, and ultimately the durability of the beam in saltwater.

manufacturing aspects include:

- Homogenization of billets prior to extrusion to ensure uniform Mg distribution and reduce segregation

- Controlled extrusion parameters to achieve consistent grain size, surface finish, and mechanical properties across the section

- Cooling rates tuned to minimize residual stress while preserving desired temper characteristics

- Precision control of dimensions and straightness, which is critical for accurate hull and deck assembly

Quality control then includes:

- Chemical analysis to verify compliance with 5086 composition limits

- Mechanical testing of tensile, yield, elongation, and sometimes toughness in the specified temper

- Visual and dimensional inspection to confirm flange/web thicknesses, radii, and straightness tolerances

- Certification according to recognized marine or product standards, ensuring traceability and acceptance by classification societies

The result is an I beam whose behavior under load, in welds, and in saltwater can be predicted with confidence.

A Distinctive View: 5086 I Beams as “Lifetime Tuners” of a Ship’s Behavior

Instead of thinking of 5086 I beams as static pieces of metal, it is more accurate to view them as lifetime tuners of how a ship behaves in its environment.

Over time:

- Corrosion thins plates and beams at different rates

- Welds experience cyclic stresses that may lead to micro‑cracks

- Added equipment and modifications change local loads on the structure

If the primary load‑bearing members are 5086 I beams, several beneficial things happen:

- The stiffness backbone of the vessel remains more stable over time because corrosion progression is slow and evenly distributed

- Repairs and reinforcements are easier because the alloy is weld‑friendly and widely supported by shipyards

- Inspection intervals can be scheduled more rationally, based on experience with 5086’s predictable degradation behavior in saltwater environments

In other words, 5086 I beams do not just survive the marine environment; they shape the maintenance and performance profile of the vessel in a favorable way. Designers who look beyond initial scantling calculations and into the vessel’s whole life cycle often end up choosing 5086 for precisely this reason.

Related Products

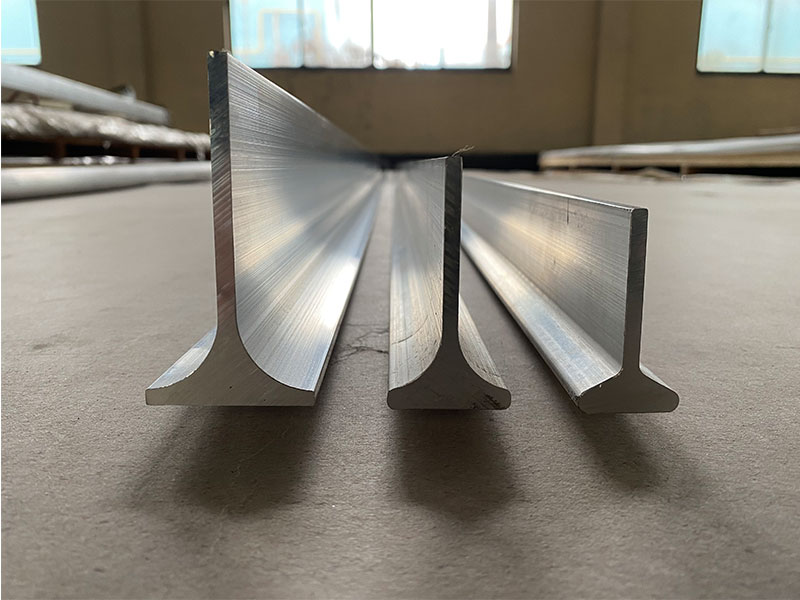

Marine aluminum I-beams

Marine Aluminum I-Beams feature the traditional “I” cross-sectional profile fabricated from marine-grade aluminum alloys like 5083, 5086, and 6061. These alloys are renowned for their outstanding corrosion resistance, especially in saltwater and marine atmospheres, making them ideal for offshore and naval construction.

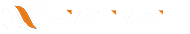

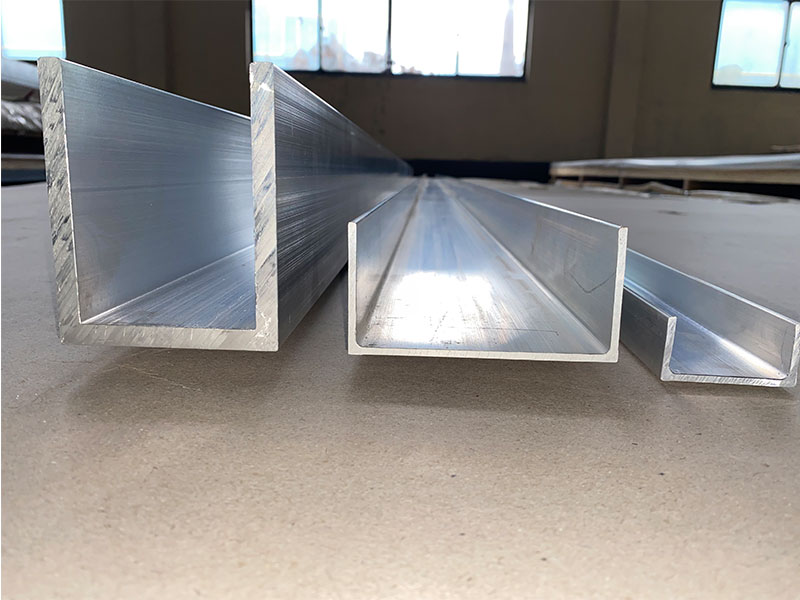

View DetailsMarine aluminum channels

Marine Aluminum Channels are U-shaped aluminum profiles produced from alloys such as 5083, 5052, and 6061, known for their excellent marine corrosion resistance and superior mechanical strength.

View DetailsMarine aluminum Z-shaped sections

Marine Aluminum Z-shaped Sections are fabricated from premium marine-grade aluminum alloys such as 5083, 5052, and 6061. These alloys are well-regarded for their superior corrosion resistance in seawater and marine atmospheres, along with good mechanical strength and excellent weldability.

View Details5083 marine aluminum flat bar

5083 aluminum flat bars belong to the 5xxx series of aluminum-magnesium alloys, known primarily for their superior resistance to seawater corrosion and salt spray.

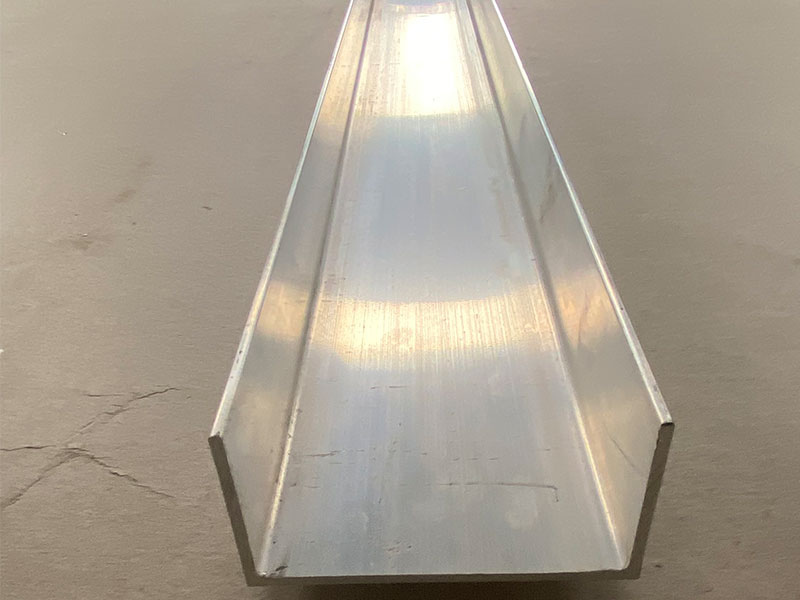

View DetailsMarine aluminum angles

Marine Aluminum Angles are L-shaped cross-sectional aluminum profiles produced from marine-grade aluminum alloys such as 5083, 5052, and 6061.

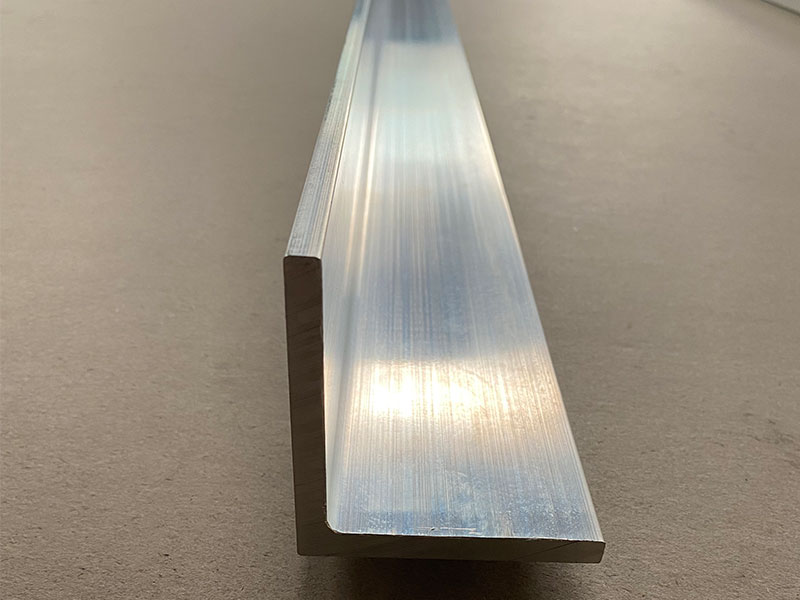

View Details6061 marine aluminum round bar

6061 aluminum belongs to the 6xxx series alloys, alloyed primarily with magnesium and silicon. In the T6 temper, it undergoes solution heat treatment and artificial aging, resulting in enhanced mechanical properties while maintaining excellent corrosion resistance.

View DetailsRelated Blog

5083 5086 6061 6082 marine aluminum channel

IntroductionMarine aluminum channel is an essential structural product in shipbuilding, offshore platforms, marine fittings, and related coastal infrastructure. Compared with steel.

View Details5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams for High Strength Marine Engineering

What Makes 5086 Marine Aluminum Special?5086 aluminum alloy is known for its superior corrosion resistance, high anodizing performance, and excellent weldability, making it a popular choice for marine applications.

View Details5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams for Custom Marine Vessel Design

Aluminum 5086 is a high-strength, corrosion-resistant alloy strategically engineered for marine applications. Its benefits, such as excellent real-world longevity and ease of customization, make it a favored choice for shipbuilding or repair processes.

View Details5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams for Saltwater Resistant Marine Ship Design

5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams: The Structural Spine of Saltwater‑Resistant Ship DesignAmong all the aluminum profiles applied in marine engineering, 5086 marine aluminum I beams sit in a special category: they are not just another “section shape,” b.

View Details5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams for Offshore Boat Frame Support

5086 Marine Aluminum I Beams are a premium grade structural component extensively used in the offshore marine industry. Renowned for their exceptional combination of high strength, corrosion resistance, and lightweight properties.

View Details

Leave a Message